As part of By Lawyers continual commitment to enhancement, the By Lawyers Wills publications in each state now feature more automated wills, particularly for LEAP users. There is improved automation in all wills precedents – Individual wills, Wills for couples and Wills creating testamentary discretionary trusts.

The wills precedents are available in folder ‘C. The Will’ on the matter plans in By Lawyers Wills publications in each state.

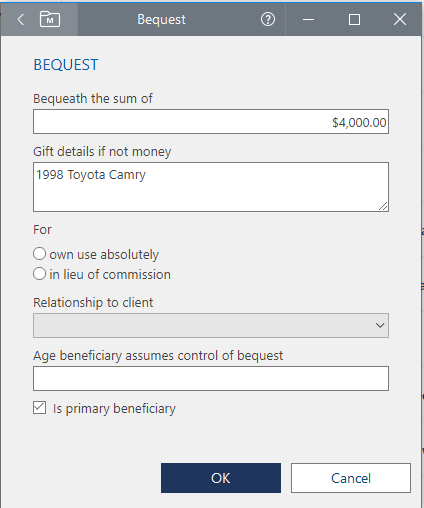

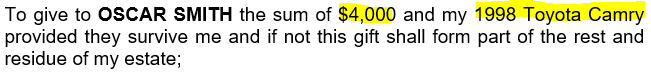

Fields have been added to the bequest clauses in all wills. This allows users to populate the precedents with any information they have completed in the ‘Bequest’ table type in a LEAP wills matter. This applies for each beneficiary added to a LEAP matter:

The bequest clause in all automated wills now provides for up to four beneficiaries. The clauses will now automatically include information based on whether a sum, a gift, or a sum AND a gift, have been completed in the table type for the LEAP matter:

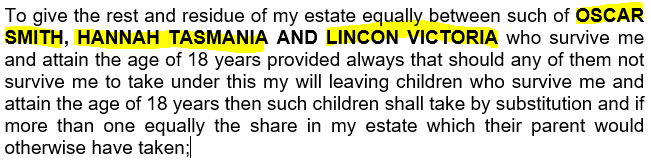

LEAP users can select ‘Is primary beneficiary’, which will add the beneficiary to the residue clause:

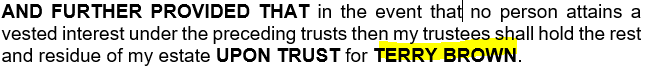

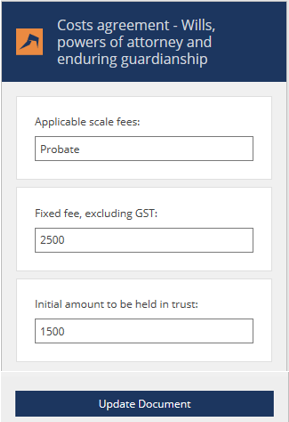

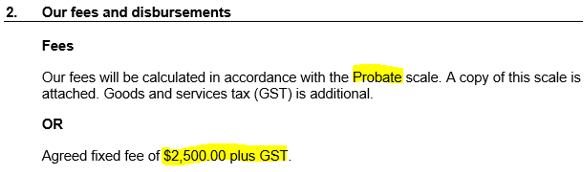

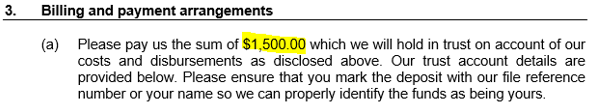

Introduction of the LEAP for Word add-in allows LEAP users to also complete additional information in a will. This functionality prompts the will-drafter for such input as the person to whom the testator wishes to bequeath their residuary estate:

For further information on using the LEAP for Word add-in, see the helpful article ‘Working with By Lawyers precedents’ available in Folder A. Getting the matter underway, on the matter plans in all By Lawyers publications.

Please do not hesitate to contact By Lawyers with any questions of feedback on these enhancements: askus@bylawyers.com.au